An update to the Violence Against Women Act is being celebrated as an important step towards protecting native communities, women and children.

“We have an ongoing crisis of violence in Alaska," said Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski. "More than half of women in the Alaska women 2020 victim survey have experienced intimate partner violence, sexual violence or both in their lifetime."

Sen. Murkowski led a bi-partisan group of lawmakers to get the reauthorization done. She has worked with many Alaska native women to strengthen and improve the law since its last reauthorization in 2013.

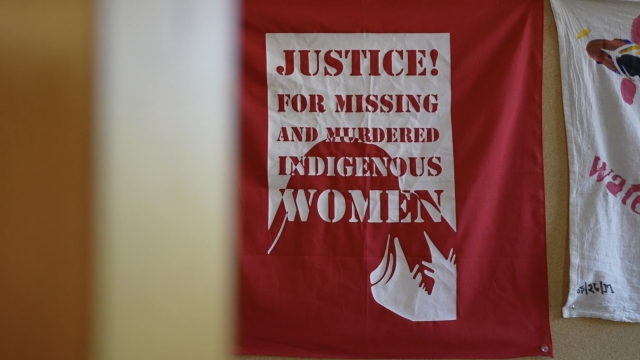

The Violence Against Women Act – also known as VAWA - is a huge deal in Indian country because of its protections for Indian women.

According to the Department of Justice, which tracks violent crime in native communities, native women experience some of the highest rates of violence. Most of those crimes are committed by non-natives.

VAWA was first passed 1994 when then-senator Joe Biden championed it, saying "My dad always said fight back against abuses of power.”

The law has since been reauthorized four times since its passage.

Sarah Deer is a Muscogee Nation citizen, an expert on tribal law and a MacArthur fellow. She helped get the law reauthorized in 2013 and says this new version is even better for native communities.

"The 2022 reauthorization restores tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians for a series of crimes that native people and tribal nations have been asking for ever since 1978 ," Deer said.

In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court stripped tribal courts of their right to prosecute non-Indians when they commit crimes within the reservation boundaries. The case was called Oliphant v. Suquamish. Deer says it was a huge blow to tribal sovereignty, but the new reauthorization of VAWA reverses some of that.

"Now with the '22 version, it's been expanded to a series of other crimes, which have been very difficult for tribes to deal with without authority over non-Indians," Deer said. "It's not a complete Oliphant fix, you know, like bribery is not in there. It's mainly violent crime, but it is another step in the right direction."

The previous version only allowed for tribal nations to prosecute non-natives for domestic violence.

The new bill will allow prosecution for child abuse, sexual violence, sex trafficking, stalking and violating protection orders. It will also allow tribal courts to prosecute a non-native who assaults a tribal police officer.

Elizabeth Reese, a citizen of the Pueblo of Nambe and a professor of tribal law at Stanford, testified before Congress before the new version of VAWA was passed.

"Expansion to adjacent crimes would create a more equitable system for prosecutors and defense counsel to navigate, and that is because the vast majority of criminal cases in the United States are resolved, not a trial, but by plea bargaining," Reese said.

The new bill commits more than $86 million to tribal justice programs which gives the act some teeth.

Deer says she’s happy with the expanded jurisdiction but says tribes need to be fully able to prosecute non-natives for any crime they commit against Indians on their own land.

"It's about we are ready to help ourselves and what we need is for Congress to be part of that project with us so that we can finally once and for all, deal with this," Deer said.

The act will be up for renewal again in 2027.